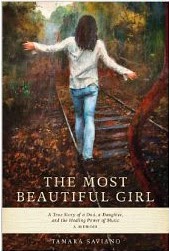

The Most Beautiful Girl

By Tamara Saviano

When I saw the title of Tamara Saviano’s memoir, The Most Beautiful Girl, I immediately thought of the Charlie Rich song from my young Navy days: “Hey, did you happen to see the most beautiful girl in the world? And if you did, was she crying, crying?”

And it is the song the title refers to. Saviano’s dad sang it to her as a child. She is now a Grammy-winning music producer and business consultant in Nashville, Tennessee. While at Johnny Cash’s funeral in 2003, she realized she needed to make peace with the memory of her father. Bob Ruditys had died two years earlier and had not spoken to her for the last ten years of his life.

The Most Beautiful Girl, subtitled “A True Story of a Dad, a Daughter, and the Healing Power of Music,” is about growing up with an abusive father, living with a severed relationship, and coming to terms with that relationship years after his death.

Saviano recalls a life-changing moment at age 15, when she discovered her mother’s old letters to Bob and came across this line: “I tricked you into marrying me by letting you believe the baby was yours.” The letter was dated a month before Tamara’s birth in 1961.

She writes, “Reality sets in: Dad might not be my biological father. On one hand, I feel relief. Part of me hates him. The man is a mean drunk and I have watched him beat my mother down emotionally and physically for years. He abuses me, too. Mom might be stuck, but I always know I will get out some day. I am a survivor. At the same time, I am enormously sad. A bigger part of me loves Dad in spite of his drunkenness and abuse.”

Much of The Most Beautiful Girl is devoted to the family dynamics of her youth—the contrast of sometimes playing and singing together and sometimes living in fear of an abusive alcoholic who beats his wife and children. Tamara’s three younger brothers turn to violence, drugs, and alcohol. She turns to men, drugs, and alcohol. She marries, has a child, gets divorced. Her ex-husband is sent to prison for sexually abusing their daughter.

Saviano’s random switching between past and present tense in the first part of the book can be jarring. While the middle section stays smoothly in the present, she reverts to the past-present bumpiness toward its end. Even for a memoir, there is a little too much “me.” Some readers might find the tone self-indulgent, with overall descriptions of people in Saviano’s life underdeveloped. They come across as tools rather than rich characters with lives and motivations. For example, she doesn’t address how her actions and attitudes make her mother feel. I had to search through the entire book to find her mother’s name—Sandra.

Toward the end of the story, Sandra explains to her daughter how she asked Bob to help her find an abortionist and he refused; he said he would marry her. Saviano doesn’t mention that this conflicts with the letter she read at age 15. The discrepancy is never resolved and the reader is left wondering what really happened.

The book picked up interest for me in the second half, when Tamara, at age 26, begins the search for her birth father after convincing her mother to divulge his name—Mike Saviano. She eventually changes her name from Ruditys to Saviano, permanently alienating her parents.

I would have liked to read more about Saviano’s transition from a beaten-down Wisconsin woman to the Nashville professional who is so well-respected that Kris Kristofferson seeks her out to be his publicist. She does talk about finding a counselor, and she provides a thin timeline of events in the healing process. To me, the redemption story is of more interest than the details of fighting with her parents. It’s a truly amazing feat to go as far in life as she has. Readers would enjoy traveling with her and cheering her on. This is an excellent story of someone who not only survives but overcomes and flourishes. I only wish she’d shared more about that process instead of jumping to the finish line.