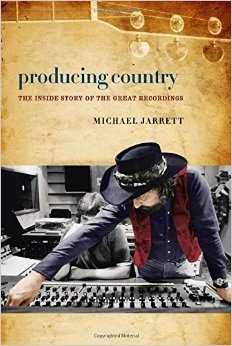

Producing Country: The Inside Story Of The Great Recordings

By Michael Jarrett

Producing Country: The Inside Story of the Great Recordings examines how the process of recording country music has changed since Ralph Peer began capturing performances on acetate in 1927. “Musicians make music. Producers make recordings,” explains author Michael Jarrett, an English professor at Penn State University.

He interviewed 51 record producers for what he refers to as “this oral history of country music production.” He writes, “I’ve organized chapters around recordings—songs and albums—arranged chronologically by original release dates. In most cases, producers provide commentary on their own working methods.”

Because I’m the author of published biographies on Marty Robbins and Faron Young, and a lifelong fan of this music genre, I looked forward to reading Jarrett’s book. He divided the book into four sections, each consisting of interview excerpts to describe four eras of recording technology: cutting tracks, taping tracks, multitracking, and encoding tracks. Jarrett explains, “Each era is characterized by an emergent technology that redefined production, effectively remaking the role of producer.”

Legendary guitarist Chet Atkins—and a chief architect of “the Nashville Sound”–summarized the changes in technology: “At first we recorded in mono and, then, eventually went to stereo two-track. . . . Les Paul came up with that eight-track machine and, then, with the sixteen and so on. . . . I told Les I was going to kick his ass for that. It caused me to have to do a lot more work and hire a lot more people.”

Shelby Singleton described making a hit out of “Harper Valley P.T.A.,” written by Tom T. Hall: “I liked the song. But I didn’t have a girl singer that I thought it fit. I had it in a desk drawer for three or four months. A disc-jockey friend of mine was managing a girl named Jeannie C. Riley.” Singleton told the friend, “Bring her by here. I’ve got a song I think is a hit if she’s got the image that I want to sing this song.” She did. The reader isn’t given the rest of the story–that this award-winning song in 1968 made Jeannie C. Riley the first woman to top both pop and country Billboard charts.

Too many short quotes from too many producers about too many people make Producing Country a choppy read. I couldn’t follow the thread about the technology changes. The quotes are sometimes about technology, sometimes about working with an artist, sometimes about numerous other topics. It’s often hard to find the point of why a particular sequence was chosen. As one example of many, a page by Jimmy Bowen carries the title of Reba McEntire’s song, “Whoever’s in New England.” But the article is a general discussion about developing a sound. The song is never mentioned, and the only reference to Reba is, “. . . a sound develops for Reba McEntire. A sound develops for George Strait.”

Probably a quarter of the book has nothing to do with country music. A more accurate title would be Producing Country, Mostly. Jerry Kennedy, who produced 26 Mercury albums for Faron Young, was interviewed, as was Faron’s Capital Records producer, Ken Nelson. But Faron is left out of the book. Although Merle Haggard and Buck Owens receive attention, the Bakersfield Sound does not.

In addition, the album/song choices certainly aren’t “the great recordings.” Where is the mention of Gunfighter Ballads, a Marty Robbins album that has remained popular for more than fifty years? Instead, we read about someone’s mid-1980s band called the Cowboy Junkies. It’s fine to cover a wide spectrum of recordings, if that’s the intent, but the title shouldn’t suggest these are great—and country–recordings.

Producing Country may entertain readers already familiar with music production and these 51 producers. But lengthier excerpts that told complete inside stories would have allowed readers to peek behind the scenes of their favorite recordings.