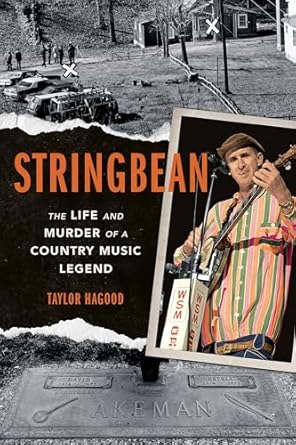

Stringbean: The Life And Murder Of A Country Music Legend

By Taylor Hagood

Stringbean was the stage name of David Akeman, a star of the Grand Ole Opry and the television show Hee Haw. Wearing a long nightshirt and pair of pants belted together below his thighs, the embodiment of a human string bean, he worked his way into the hearts of fans around the world with his banjo, his singing, and his comedy. He was just 58 and his wife, Estelle, 59, when they returned home from an Opry performance on November 10, 1973, and were shot to death by intruders searching for money in the Akeman farmhouse.

In Stringbean: The Life and Murder Of a Country Music Legend, author Taylor Hagood offers a well-researched academic book he calls “a three-for-one: biography, true crime, and courtroom drama.” An English professor at Florida Atlantic University, who also plays the banjo, Hagood first learned of Stringbean when his parents took him to the Country Music Hall of Fame in Nashville in 1987.

Kentucky native David Akeman became a professional entertainer during the Great Depression. Improving his skills as banjoist and singer in regional bands during the 1930s, he called himself “Stringbean” and “The Kentucky Wonder.” His dream of performing on the Grand Ole Opry became a reality when he joined Bill Monroe and the Bluegrass Boys in 1942. Stringbean developed his costume and comedy routine while demonstrating the banjo style that helped originate the musical genre known as “bluegrass.” Famed Opry banjoist and comedian Uncle Dave Macon served as his mentor and performance role model. “He was one of the greatest entertainers I ever knowed, and I’ve knowed a lot of them,” Stringbean once said.

When Hee Haw hit the television airwaves in 1969, Stringbean became a regular on the show. In one weekly segment, he played a scarecrow standing out in the corn field with a crow on his shoulder. In another, he read letters that he carried “right here next to my heart, heart, heart.”

Stringbean and Estelle were frugal, living in a small house in the country and even sharing napkins to save money. Married in 1945, both previously divorced, they were mostly inseparable. They shared a passion for fishing. Whether or not Stringbean knew how to drive, Estelle drove them wherever they went. He told friends that being dependent on her to drive him meant he never had to leave home without her. They purchased a new Cadillac every year for tax-deductible business purposes and drove an economical personal vehicle when not traveling to shows.

Remembering those Depression days of poverty, Stringbean carried a large roll of cash in the front pocket of his bib overalls. What began as a gag with one large bill rolled around smaller ones became an actual roll of large bills as he became wealthier. Since the 1950s, he’d talked about his goal of becoming a millionaire, with comments that he and his five-string banjo would make a million. “String was known around the country music family not only for carrying cash but for his distrust of banks,” the author writes. “The rumor began to spread that the couple had amassed a small fortune through their frugal living and kept it hidden at home. His friends worried.” The Akemans did have bank accounts, and they placed some of their money in bank strongboxes, but their fortune was never documented. They died without wills.

When Opry stars were questioned after the murders, the author writes, “As for the motive, none of these stars could think of the Akemans having any enemies, but practically all of them spoke of String’s tendency to carry that big wad of money. They had warned him that doing so would get him hurt or killed, but he had kept on. Moreover, there had been rumors about money in the house.” The killers found only $200. They missed the rolls of cash in Estelle’s bra and Stringbean’s overalls, totaling $5,700.

John Brown and his cousin, Doug Brown, were convicted of the murders in a trial covered in detail in the book. Doug’s brother, Charlie, who lived three miles from the Akemans and was an acquaintance, was implicated in the crime but never charged. Doug died in prison. John was paroled in 2014, an action Grand Ole Opry star Mac Wiseman called “a great miscarriage of justice.” Wiseman and fellow entertainers such as Jan Howard had appeared at every parole hearing throughout four decades, seeking to keep the Browns in prison.

Hagood’s scholarly treatment of the Stringbean story adds to the history of both country music and the law enforcement processes in 1970s Nashville. Published fifty years after the murders and their investigations, this biography is divided into chapters and subsections with headings that list dates and major events. The first two thirds tell of Stringbean’s life and the last third deals with the aftermath of the murders. The book offers thoroughness and readability as it brings the memory and accomplishments of Stringbean back to life.