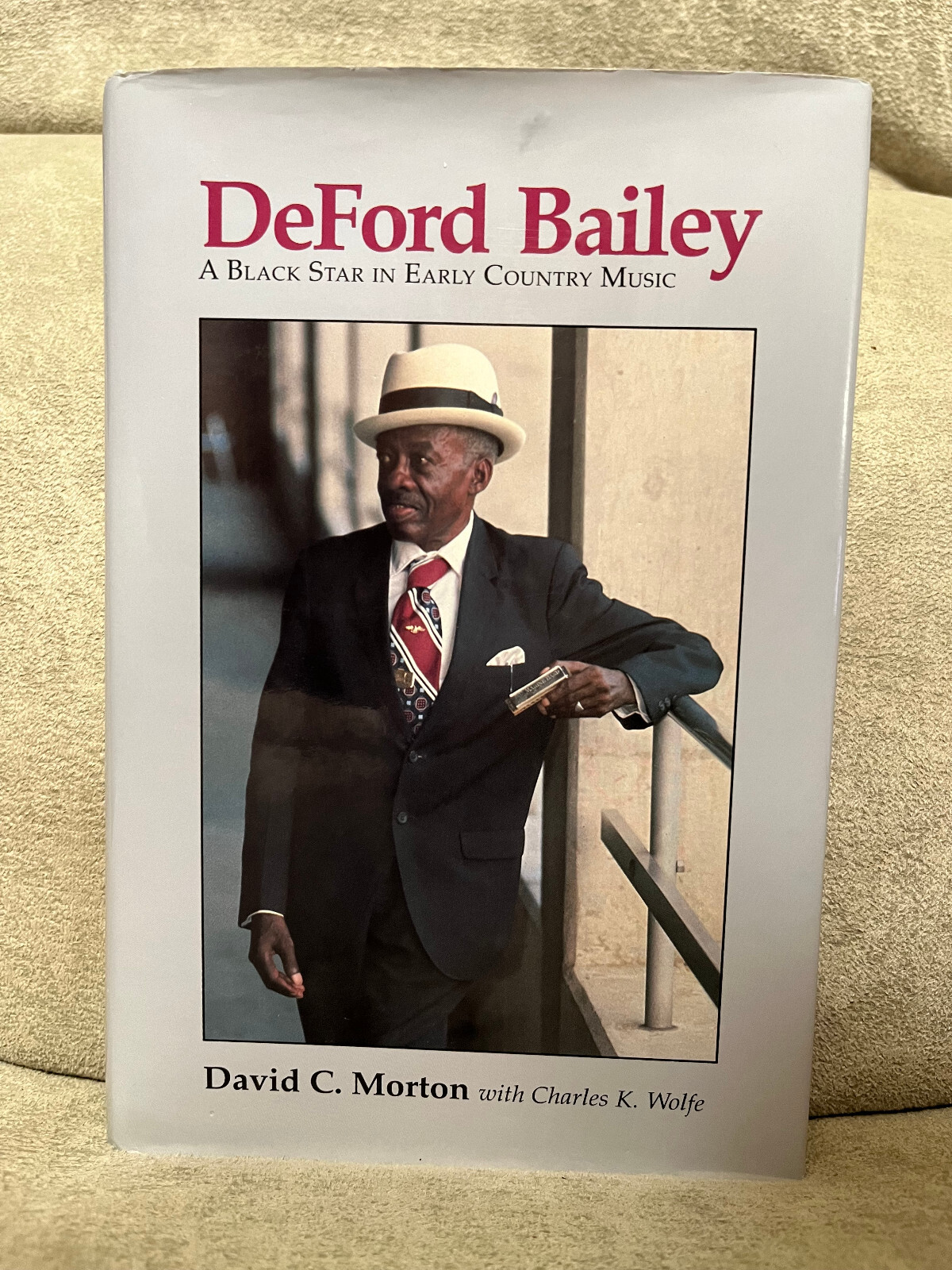

DeFord Bailey: A Black Star in Early Country Music

By David C. Morton

The Country Music Foundation Press recently partnered with The University of Illinois Press to reissue its out-of-print 1991 biography, DeFord Bailey: A Black Star in Early Country Music. The author, David C. Morton, first met Bailey when he went to the “Harmonica Wizard’s” apartment for an interview in 1973. They became friends, and Bailey eventually asked Morton to write his biography. “He wanted a biography done so his grandchildren and later generations would know ‘the truth’ about him,” Morton explains in the introduction. “The result is basically the story of his life told to me during various visits and conversations.” Morton also interviewed numerous friends and Grand Ole Opry members as part of his research. He collaborated with historian Charles K. Wolfe, who is credited as the book’s co-writer.

The grandson of a former slave who was a superb fiddler, Bailey grew up in a musical family. He was born in 1899 and spent more than a year in bed with polio before old enough to go to school. As a result, he never reached five feet or 100 pounds in adulthood. While bedridden, he learned to play several musical instruments and focused on the harmonica in his teen years. When WDAD, the first radio station in Nashville, began broadcasting in 1925, Bailey was one of its original performers. In early 1926, he joined WSM, before its Barn Dance became the Grand Ole Opry. “Week after week DeFord continued to delight audiences and bring in mail as well as telegrams and phone calls with special requests,” Morton writes. His music brought in the first 3,000-mile telegram WSM ever received.

As the Opry grew in popularity, its performers hit the road during the week. Bailey traveled all over the country as part of those shows. Although often the biggest draw on a tour, he could not sleep in hotel rooms or eat in restaurants with his white traveling companions. They did what they could to look out for him in the Jim Crow South, but he sometimes had to eat and sleep in the car. When Roy Acuff and Bill Monroe first joined the Opry, they both took Bailey on the road with them because he brought in a much bigger crowd than they did.

Bailey also sang and played guitar and banjo. A left-handed player, he held the instruments upside down rather than restringing them. When he worked up new music to play on the Opry, he was told to stick with his standards. Then came the ASCAP-BMI feud in 1940, when radio stations boycotted ASCAP songs and would only play BMI music. Most of Bailey’s songs were ASCAP copyrights, music he had finetuned over a period of years. WSM fired him in May 1941 for not learning new music.

With a wife and three young children, he had no job and no severance pay, after 15 years as an Opry star. He’d never complained about being paid considerably less than the white performers, and he never received any compensation. “When they turned me out, I didn’t have a cent, but I had sense,” he told Morton. “I knowed I could make it on my own. I walked out of WSM with a smile.” He started a shoeshine parlor, rented out rooms in his family home, and sold meals to construction workers. In its 97-year existence, the Opry has never had another black star.

By the time Morton and Wolfe met Bailey in 1973, he was divorced and living in a rent-subsided high-rise apartment in the Edgehill section of Nashville. He died in 1982, the biography was published in 1991, and he was inducted into the Country Music Hall of Fame in 2005. I’m glad DeFord Bailey: A Black Star in Early Country Music has been reissued. His story should not be forgotten.