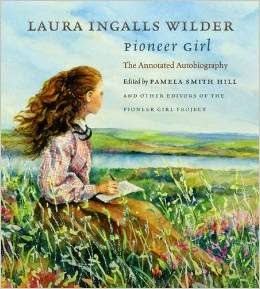

Pioneer Girl: The Annotated Autobiography

By Laura Ingalls Wilder, with Pamela Smith Hill, editor

Laura Ingalls Wilder told an audience in 1937: “I realized I had seen and lived it all—the successive phases of the frontier, first the frontiersman, then the pioneer, then the farmers and the towns. Then I understood that in my own life I represented a whole period of American history.”

In six notebooks, she’d recorded the story of her youth, from her first memories until her marriage to Almanzo Wilder sixteen years later. This nonfiction manuscript, written in 1930 for adults, was never published–until now. The South Dakota Historical Society Press recently released Pioneer Girl: The Annotated Autobiography, with Pamela Smith Hill as editor.

“Wilder wrote her life story straight through—the original manuscript had no section or chapter breaks,” Hill reports in the introduction. “Some of her marginal notes reveal that, from the beginning, she intended Pioneer Girl as both a private family narrative written from a mother to her daughter, and as a rough manuscript that would ultimately be edited for publication.” The daughter, Rose Wilder Lane, was already a well-known author. The two women submitted several versions to publishers in the early 1930s but were unsuccessful in getting the story published. They then turned to fiction, using excerpts from the manuscript to build what became the Little House series of children’s books.

I grew up with those eight books, from Little House in the Big Woods through These Happy Golden Years. When I began writing my first book, also about a one-room country school and a rural South Dakota childhood, I reminded myself I had twenty years to catch up with my role model. Wilder drafted her first manuscript at age 63.

Pioneer Girl: The Annotated Autobiography provides a typed version of the original hand-written manuscript, along with voluminous footnotes to explain details and compare earlier drafts. The footnotes make a story in themselves. They give us a peek at the later married years of Laura and Almanzo and the relationship of mother and daughter as Wilder and Lane worked on the books.

For example, the book By the Shores of Silver Lake contains a section on building a railroad. “The level of detail suggests that Lane, who had no firsthand knowledge of railroad construction, worked closely with Wilder to recreate it,” Hill explains in one footnote. “Lane’s diaries reveal that she and her mother were frequently in each other’s company during the summer of 1930. Lane undoubtedly asked her mother to provide specific details. . . . Ultimately, however, the women probably drew on Almanzo’s memories of railroad construction.”

The reader experiences some of the struggle and decision-making involved in turning a real life into fiction. Hill and her assistant editors skillfully show how the novels were developed from the original manuscript. Correspondence between the two women traces the shaping of the stories and explains when Wilder wanted to make a point for her youthful readers and when she was adamant about using events as they had happened. Some circumstances were softened, such as the loss of Laura’s dog, Jack. He died of old age in the Little House series. In real life, Pa Ingalls gave Jack away when selling a pair of horses.

All names mentioned in the manuscript have been thoroughly researched, with footnotes to quote census records, explain which names were unidentified or fictionalized, and summarize the remainder of people’s lives. Quotations from newspaper articles help to support the events Wilder described.

Most of the stories in Pioneer Girl I already knew. However, mention of a brother named Freddy came as a surprise to me. Wilder writes, “Little Brother was not well and the Dr. came. I thought that would cure him as it had Ma when the Dr. came to see her. But Little Brother got worse instead of better and one awful day he straightened out his little body and was dead.” A footnote explains, “He was nine months old. His grave location is unknown. Other versions of Pioneer Girl shed no additional light on the nature of his illness or the cause of his death.” Soon after Freddy died, the Ingalls family moved to Burr Oak, Iowa, for a year. The Little House books do not mention that period.

Surviving artifacts add life to the stories. Wilder writes, “So Pa went to his hunting and we feasted on geese and duck. Ma and I saved all the feathers and that fall we made a large featherbed and four large pillows from the best of the feathers. When I was married Ma gave me two of these pillows and they are good yet, as soft as the newly bought ones.” A footnote tells us, “These pillows are still in the Wilder home in Mansfield, Missouri.”

This annotated autobiography has only a few weaknesses. While the unpublished drafts frequently offer facts not in the original manuscript, repeated comparisons of fictional versions add no value. Hill sometimes talks down to her readers, sounding like a high school English teacher. Her repeated explanations about the difference between fiction and nonfiction are unnecessary, as is telling us what a memoir is.

Other than these minor issues, Pioneer Girl: The Annotated Autobiography is an enthralling read. It feels like holding a piece of history in your hands.