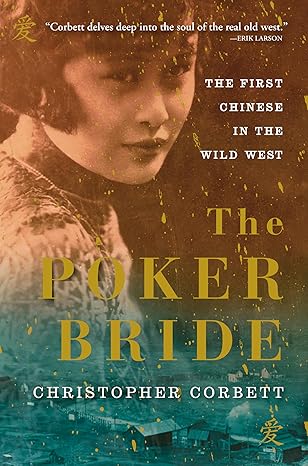

The Poker Bride

By Christopher Corbett

Polly Bemis became a nationwide news sensation when she arrived in the town of Grangeville, Idaho, in 1923, coming out of the mountains for the first time in fifty years. The 70-year-old Chinese woman, who had never heard of trains or automobiles or electricity, wanted dental work and eyeglasses. About emigrating from China in 1872, she told a reporter in her heavy accent, “My folluks in Hong Kong had no grub. Dey sellee me . . . Slave girl. Old woman she shmuggle me into Portland. I cost $2,500. Don’t looka it now, hmm?” She then described a Chinese man taking her in a pack train to Warrens, Idaho, where a Chinese miner claimed her as his purchased sex slave. The miner lost her to Connecticut-born gambler Charlie Bemis in a poker game. Bemis married Polly in 1894, possibly to prevent her deportation, and the childless couple lived on the banks of the Salmon River until death.

The Poker Bride tells as much of Polly’s story as author Christopher Corbett could piece together from historical records and old-timers’ memories. The book’s subtitle, “The First Chinese in the Wild West,” refers to Chinese immigration in the nineteenth century rather than to Polly. It documents the flood of Chinese laborers who came to the United States looking for wealth in the Gold Rush or to earn money building the Transcontinental Railroad but who became “the yellow peril” to many American citizens. Sixteen pages of bibliography exhibit Corbett’s extensive research.

By the time Polly reached the United States, two decades after gold discovery, Chinese men were seen as a threat to American workers, both men and women, due to their vast numbers and their willingness to perform quality work for low wages. They took any job available, from mining to housekeeping. A “Chinese Must Go” movement began in San Francisco and spread rapidly. The Chinese Exclusion Act, passed by Congress in 1882, attempted to stop immigration and increase deportation. Some states prohibited Chinese from owning property, while assessing them with extra taxes. Census takers frequently ignored them. Corbett writes, “Polly Bemis came into a country where Chinese immigrants coming off ships in San Francisco were welcomed with a gauntlet of abuse and catcalls and were pelted with rocks as they walked up from the docks to Chinatown, the only safe place for them in the booming port.”

American labor unions encouraged anti-Chinese rallies, held as far east as Denver. Chinese residents were physically driven out of numerous towns, their possessions destroyed, their homes and businesses burned.

Chinese men usually arrived without families, partly because their culture prohibited respectable women from traveling and partly because of male-oriented work sites. Having no chance of building relationships with American women, they resorted to purchasing sex slaves imported from China. Most of the thousands of Chinese women sold into slavery and shipped to the United States died of venereal disease. Polly escaped this fate. Before her marriage, she ran a boarding house in Warrens and was so well-liked that many of her friends refused to acknowledge in later years the possibility she might have been a prostitute.

“What Polly Bemis did most successfully was survive,” Corbett writes. “She survived an experience and a system that killed most of the young women who entered it.” Two homesteaders who were neighbors of the couple took care of Polly in her later years and preserved her memory after her death. Although Polly could not read or write, she could count money and was a proficient gambler. She fished and gardened and provided enough energy for both her and her lazy husband. When Charlie one day drew her attention to a busy anthill, she told him, “Bemis, if you’d work um like these ants, we wouldn’t be poor folks.”

Corbett shows his skill as a journalist and reporter in his ability to find information and package it into a readable story. The amount of historical research that went into this book is noteworthy, and arranging it must have been a daunting task. Still, a better arrangement could have lessened the repetition of introducing and reintroducing sources while describing events in The Poker Bride. Corbett repeatedly mentions “the day Polly rode into town.” She finally gets off her horse halfway through the book, followed by twelve pages on Chinese prostitutes before the author, once again, writes, “Polly Bemis dismounted from the saddle horse in Warrens in the summer of 1872.”

Additional photographs would have added interest. There are none of Charlie and only two of Polly, even though Corbett spent several pages describing photos of the couple and their home. “By the time anyone got around to photographing Polly Bemis,” he writes, “she was no longer the beautiful Chinese courtesan or exotic slave girl of the story, but a sturdy old woman with her hair tucked up in a neat bun and often wrapped with a bandana.”

While readers who expect a book about a poker bride may be disappointed to find mostly a historical documentary, The Poker Bride provides valuable knowledge on Chinese contributions in building the West.