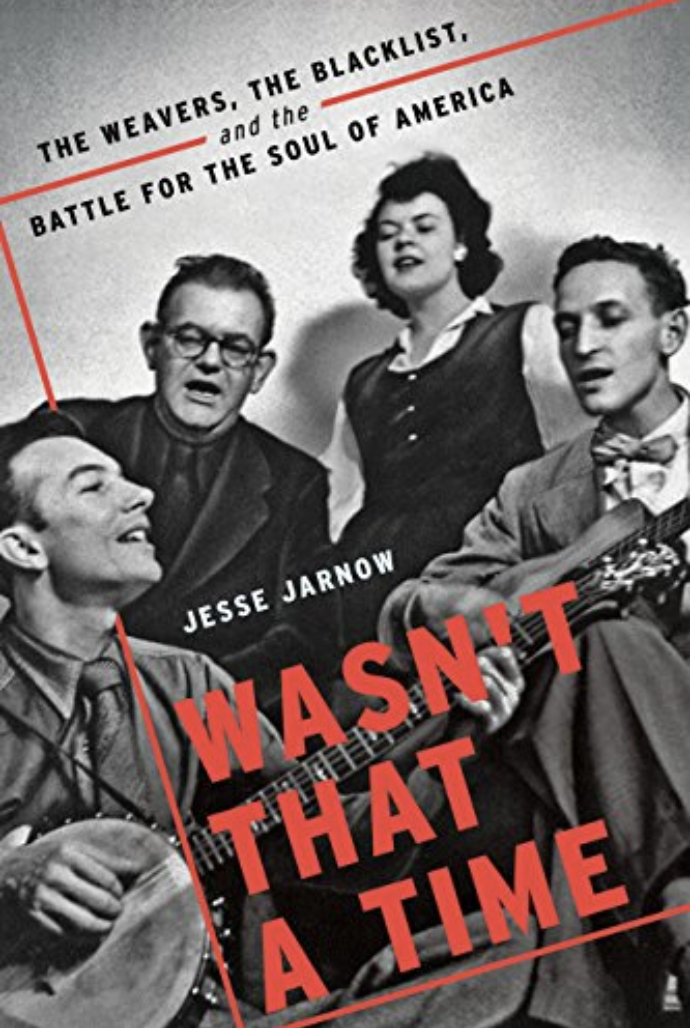

Wasn’t That A Time: The Weavers, The Blacklist, And The Battle For The Soul Of America

By Jesse Jarnow

Wasn’t That a Time: The Weavers, the Blacklist, and the Battle for the Soul of America is the story of a singing group that brought folk music to the pop charts in spite of having its own career derailed by the Red Scare following World War II.

In his thoroughly researched book, author Jesse Jarnow intermixes history of the Weavers, effects of the U.S. government’s blacklist, and biographies of the band members. Pete Seeger joined the American Communist Party in the 1930s because, Jarnow writes, it was “a powerfully anti-racist pro-labor entity.” He and Lee Hays “often shared political stances and the dream of a singing labor movement.” Following Seeger’s U.S. Army service during the war, the pair founded the Weavers in 1948. Their earlier band, the Almanac Singers, had included Woody Guthrie.

Seeger and Hays, along with junior members Ronnie Gilbert and Fred Hellerman, believed in using music to bring people together and give voice to the downtrodden. The author describes how their songs spread messages ranging from support of labor unions and workers’ rights to countries fighting for independence.

Hays co-wrote the song that became their anthem, “Wasn’t That a Time.” After verses about the Revolutionary War, the Civil War, and World War II, the refrain asks, “Wasn’t that a terrible time?” Then the song moves into the present: “And now again the madmen come and should our victory fail? There is no victory in a land where free men go to jail.” The song ends with a rallying cry: “Our faith cries out we have no fear. We dare to reach our hand . . . Isn’t this a wonderful time!”

The U.S. Supreme Court ruled in 1951, in the case of Dennis vs. United States, that advocating communism was supporting the overthrow of the U.S. government and was not covered as freedom of speech. The Weavers were blacklisted, with concerts and recording sessions cancelled. “More of the Weavers’ harassment was at their performances,” the author writes. “They hadn’t seen the last of the American Legion, either, who continued to make cameos throughout the remainder of the band’s career, turning up in picket lines with Veterans of Foreign Wars and other groups.” The Weavers stopped playing at the end of 1952, when they could no longer get bookings.

As happened to numerous entertainers during this period, the four band members were subpoenaed by Senator Joseph McCarthy’s House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC). When Seeger testified at a HUAC hearing in 1955, he was charged with contempt for not completely answering the questions. His offer to sing his songs for the committee was rejected. “After his testimony,” the author writes, “Pete broke through the blacklist, however briefly. Outside the courtroom, in the hallway, Pete’s banjo finally returned to his hands, he bid adieu to the committee, singing ‘Wasn’t That a Time’ for the cameras and the evening news.”

Seeger stayed busy with solo performances until the Weavers reunited in late 1955. He left permanently in 1958, to pursue a solo career, and was replaced by Erik Darling. Throughout the years, for the remainder of the musicians’ lives, there would be occasional reunions. Hayes died in 1981, Seeger in 2014, Gilbert in 2015, Hellerman in 2016, and Darling in 2018.

Peter, Paul, and Mary took Weavers songs such as “If I Had a Hammer” to lasting fame. The Beach Boys, Byrds, and Grateful Dead are among the musicians who credit the Weavers as a major influence in their careers.

As source material for Wasn’t That a Time, Jarnow searched through Seeger’s FBI files, Hays’s papers in the Smithsonian Institution, Gilbert’s boxes of correspondence, and Hellerman’s journals. He conducted interviews with family members and musicians influenced by Weavers music. The research is excellent, although the infrequency of dates and the juxtaposition of events make following timelines difficult. The focus is on events rather than personal lives.

Wasn’t That a Time will appeal to anyone who remembers Pete Seeger and the Weavers, as well as anyone interested in pop-folk music history or the effects of the Red Scare blacklist. While the U.S. government did its best to destroy this folk-pop quartet at the height of fame, the Weavers managed to produce ten hit songs that became instant American standards.

With freedom of speech always in need of protection from attack, this is a story that resonates today.