A Farm in the Hidewood — Chapter One

Diane loved Little Joe Cartwright. It didn’t matter that he was a television character she saw every Sunday evening on Bonanza.

“Hurry, Kayo. It’s almost a quarter to eight,” Diane said as she pulled on her hooded gray parka and zipped it.

“I’m coming,” her younger sister replied. “It’s only half a mile to Elm’s house, and Bonanza don’t start ’til eight o’clock.”

She stacked the plates in the white cupboard, folded and hung up the towel. At age ten, she had been doing dishes half her life. “Is Kenny coming with us?”

“He’s already there. He rode his bike over after supper.” Diane nudged her sister out the south door of their eighty-year-old farmhouse.

Kayo glanced at the full moon as she stepped out on the wooden porch and breathed in the crisp March air. “Spring’s early this year. It’s sure been a bea-u-ti-ful weekend.”

“Yeah, but we might get another blizzard. You know how unpredictable South Dakota weather is. Having the snow almost gone don’t mean it will stay gone,” Diane said. “Hurry up; we’re gonna be late.”

“Don’t be so bossy!” Kayo started walking down the road to their Uncle Elms farm. “I wish we had 110-volt electricity so we could have our own TV. Nobody else in the Hidewood Valley uses thirty-two volts.”

“Dad says what we got works fine. We don’t have money for new electrical stuff. We probably couldn’t afford a TV.”

The lack of modern conveniences didn’t bother Diane as much as it did Kayo.

Diane saw shortcomings in herself more than in her surroundings. She accepted the reality of a home without indoor plumbing or modern electricity, but she longed for self-confidence and a thinner body. People might like her better if she were prettier and less bashful. What she read in books made her want to travel and sometimes be someone else.

For now, she could dream about Joe Cartwright. Watching Elm’s television took her back to Bonanza’s Virginia City of the 1880s. After the show ended, Elm served a snack to his nieces and nephew. When the girls walked home, they discussed their TV heroes along the way. Diane said, “Wouldn’t it be great if we could get pictures of them? Imagine having the four Cartwrights, especially Little Joe, to look at every day.”

“How could we do that?” Kayo asked.

“If we wrote to the station in Sioux Falls, they’d know what to do. Let’s do it tomorrow after school.”

“Tomorrow is Dennis Falken’s surprise farewell party,” Kayo remembered. “It’s gonna be strange not having Falkens in the valley.”

“I’ve gone to school with Dennis for seven years, since I was five and he was six. He’s the cutest boy in school.”

“You like him cuz you got the same birthday,” Kayo teased. “You think that makes you special.”

In response, Diane swatted her sister. They climbed the four wooden steps of the south porch and entered the front room.

Mom paused from mending a pair of blue jeans on her treadle Singer sewing machine. “How was Bonanza?”

“Okay,” Diane answered. “Adam fell in love with a peddler’s daughter of a different religion.”

“And they split up, of course,” Keith said. “One of them falls in love every week, but they gotta get rid of the girl or it would ruin the show.”

“Oh, go back to your tractor book,” Diane told her older brother. “You wouldn’t appreciate a good story, anyhow.”

“Don’t you kids start squabbling,” Mom warned. “Where’s Kenny? It’s ten o’clock and tomorrow is a school day.”

“He’s putting his bike away,” Diane said. “I saw his headlight coming up the driveway.”

She changed the subject. “Dad, would you take us to school tomorrow? I have to bring Kool-Aid and cupcakes for Dennis’s farewell party.”

“Sure,” Dad replied. He sat at the round oak table in the middle of the front room, entering receipts in the farm record book. “I’m going to town, anyway, to buy a belt for the UB diesel tractor.” He added, as Kenny came in the door, “Now you kids get to bed.”

Diane grabbed a stack of mended clothes to carry upstairs. “Time for the nightly fight,” she said. Her brothers fought themselves to sleep every night.

She followed the two boys through the doorway and up the steep enclosed staircase, keeping a safe distance. She didn’t want to get hit by flailing arms and legs as they wrestled their way to the top of the stairs.

The children’s bedroom covered almost half the upper floor of the house. Several years ago, Dad built a dividing wall in the huge room. The girls shared a double bed on the south side and the boys shared one on the north side. This provided privacy, but no escape from the noise.

“Boys, shut up!” Kayo yelled from the girl’s side of the room.

“He started it,” Keith answered.

“That’s your answer every time, both of you,” Diane complained. “You’re fourteen, Keith. Twice as old as Kenny. You’re big enough to stop fighting.”

Fortunately, Keith and Kenny must have been tired, because they soon went to sleep. Diane preferred snoring to fighting.

The next morning, when Dad drove the 1961 Chevrolet Greenbriar onto the schoolyard, Diane looked at the white schoolhouse with pride and affection. She wondered how long Altruria had been educating Hidewood Valley children.

Since the first grade, she wanted to be a schoolteacher, sitting behind the gray metal desk and looking out at a roomful of children.

Diane knew her dream wouldn’t come true. The law required country schools to be closed in a few years, and everyone would go to school in town. Maybe she would join the Peace Corps after college and teach overseas. Today, though, even high school seemed far away. Diane thought she’d be happy to stay at Altruria forever.

The four children raced up the concrete steps and into the wooden-floored entryway.

Keith pushed Kenny out of the way as he placed his lunch box on the old wooden desk and hung his parka on a metal hook. Kenny knocked Keith’s parka on the floor when he hung his own.

“Boys, behave yourselves!” Diane warned, as Kayo opened the schoolroom door and they joined their classmates.

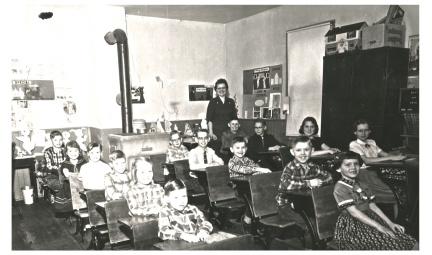

The warm atmosphere of the room wrapped itself around Diane. Sunshine through the two east windows made bright streaks on the dark board floor. Black chimney pipes curved from the caramel-colored oil-burning stove and disappeared into the north wall.

Neatly printed letters of the alphabet marched across the front of the room, making a border above two blackboards.

Four rows of varnished wooden desks with black metal legs faced the door. Each row consisted of four different-sized desks bolted to wooden runners.

Diane slid into her desk along the west wall. Looking out the window, she could see cottonwood trees and the creek that ran through the cow pasture on the far side of the schoolyard.

She glanced across the room to the portrait of President John Fitzgerald Kennedy above the east window. He looked young and handsome, unlike previous Presidents who appeared to be old men. Diane liked his strange accent when she heard him speaking on the radio.

He’d started the Peace Corps, which was the main reason she thought about joining it. That was the closest she would ever get to him.

“Good morning, children,” Mrs. Stadem said. “Please stand for the Pledge of Allegiance. We’ll follow that with a few songs.”

Fourteen children from six families slid from their desks and stood in the aisles. They placed their right hands over their hearts.

Keith and Dennis and two other boys comprised the eighth grade. Diane shared the seventh grade with Peggy Casjens.

Next came Polly Gruener, Mickey Reichling and Ruth DeYoung. Connie Casjens was the lone fifth grader.

Dean Gruener and Kayo were in the fourth grade, followed by Wendy Casjens. Kenny had the second grade to himself, and there were no first graders this year.

As they recited the Pledge of Allegiance, Diane smiled at the memory of her first years in school. She had wondered why the pledge ended with the words, “liberty and just a frog.” She later learned everyone else had been saying “justice for all.”

Dean passed out yellow paper-backed copies of The Golden Book Of Favorite Songs and the children gathered around the piano.

Mrs. Stadem played traditional tunes and they sang “America the Beautiful,” “Faith Of Our Fathers,” “This Land Is Your Land” and “Swing Low, Sweet Chariot.”

Excitement about the surprise party kept Diane from concentrating on her school work that day.

But when party time arrived, Dennis was not surprised–someone had told him. Diane felt disappointed. She liked surprises, both for herself and others. I don’t understand why someone would spoil it by telling Dennis, she thought. But he could at least have acted surprised.

Diane’s cherry-topped cupcakes disappeared almost as fast as Grueners’ famous peanut butter bars. After everyone finished eating, Mrs. Stadem said, “I have a doctor’s appointment this afternoon, so I’ll let you go home half an hour early.”

Kayo and Diane hurried west across the pasture hills, anxious to get home and write their letter. “I wonder what the picture will cost,” Kayo said. “We ain’t got no money to pay for it.”

“I’ll ask in the letter to make the price about fifty cents,” Diane said. “We can afford that. I hope it will be enough.”

That evening, the white metal letter rack by the kitchen door held a sealed envelope waiting to be mailed the next day.

Several weeks later, when the four Diekmans came home from school, Mom said, “Diane, here’s a letter for you.” She held out a long envelope with red and blue stripes down the side and a return address of the National Broadcasting Company in New York City.

With trembling fingers, Diane tore open the envelope.

© 2001 by Diane Diekman

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!