Speech at South Dakota State Fair

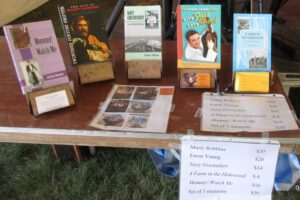

At the South Dakota State Fair in Huron, on September 3, Sherwin Linton invited me to talk about my books and my Navy career. Here is my speech. (Thanks to John Mogen for the photo.)

Thank you, Sherwin. Good afternoon to all of you. I became a mother at age fifty, while I was a U.S. Navy captain stationed in Los Angeles. I was in command of an organization of about 350 people. While living in Los Angeles, I learned that the courts can take away children from abusive parents, terminate parental rights, and offer them up for adoption. Also, that single people could adopt. I had tried to adopt for 20 years, and this time it worked.

I got matched up with two little girls—sisters—ages five and seven, who had been in foster care for more than four years. Foster care was the only life they knew. As we were learning to be a family, and I was learning to be a parent, one of the things that really concerned me was if this was normal kid behavior or was it the result of the trauma from their past. I constantly struggled to know how I should respond to their behavior.

One day I was talking to an Army lieutenant colonel who worked for me, and he asked me how things were going. I told him my latest problems, and he said, “Oh, that’s just normal kid behavior. My kids used to act like that.”

I said, “Your kids didn’t tell you they wished they could go back to their real parents.”

He said, “No, but they said they wished they had different parents.”

That was the most helpful thing anybody said to me. I often thought of his comment over the next few years as I was struggling to know how I should respond to whatever behavior was going on.

One night, one of the girls was lying on her bed, kicking and screaming. She said, “I’m gonna call our social worker and tell her I want to go back to our foster home.”

I said, “Okay, I’ll dial the phone for you, and you can tell her now.”

Silence. She said, “No, I’ll just wait till the next time she comes over, and I’ll tell her then.” I didn’t hear that threat again.

In the mild Los Angeles climate, I usually kept our windows open, and I really worried that my neighbors might call the child abuse hotline when they heard my daughters screaming, “Call the cops! She’s murderin’ me!”

But that didn’t happen. We survived. We moved to Washington, D.C., I retired from the Navy there, and then in 2010 we moved to Sioux Falls.

I tell all those stories in Mommy! Watch Me, my third memoir. I just published this this summer. It covers the first ten years of our life together as a family. In this book, I also talk about writing my first four books. While I was in Japan, I wrote the first draft of two memoirs. I finished them up and published them when I moved to Los Angeles.

The first one is A Farm in the Hidewood: My South Dakota Home. It takes place in 1963 on a farm up by Clear Lake. I talk about going to a one-room country school and butchering chickens and hauling hay bales, and milking cows, and all that farm stuff.

The second one, Navy Greenshirt: A Leader Made, Not Born, covers 18 of my 32 years in the Navy, beginning when I went to aircraft maintenance officer school, until I got promoted to captain. I was one of the first women in the field of naval aviation maintenance. In that first school, one of my classmates said to me, “I don’t have anything against women in the military. As soon as they prove they can do the job, I accept them.”

I said, “That’s exactly it. A man you accept immediately, no questions asked. But a woman has to prove herself before you’ll accept her.”

He said, “You know, you’re right. I never thought of it like that.”

And I did definitely have to prove myself. In my first squadron, my commanding officer fired me for not being assertive enough. I had worked up through branch officer, division officer, up to assistant department head, and when I heard the commanding officer had put out a new job change list, I went to the CO’s secretary to get a copy of the list, because it was my responsibility to make sure all these job shifts actually happened.

And she wouldn’t give me the list. It took about two days before she finally gave it to me. I looked at the paper, and the first thing I saw was somebody else’s name by “assistant maintenance officer.” I looked for my name, and I found it down at the bottom, in the first job I’d had when I checked into the squadron. My mouth dropped open, and I looked at her in shock, and she cringed. Then I understood why she hadn’t wanted to give me the list. She was hoping my bosses would tell me that they had fired me, but they didn’t.

Nobody ever explained to me what had happened, so I figured it out for myself. I had been set up. When the maintenance officer went on leave, I was acting department head, and I was really excited to be in charge of the maintenance department for a week. But for that whole week, the commanding officer never talked to me. He only talked to the maintenance master chief, who worked for me. I thought, well, I’m in charge; he’s supposed to be talking to me. But he’s the commanding officer, and I’m only a young lieutenant, so he must know what he’s doing.

Well, he knew what he was doing, all right. Apparently, they were all waiting to see how I would respond. Whether I would say, “Hey, boss, I’m in charge. You’re supposed to talk to me.” But I didn’t, I didn’t say anything, I failed, and I got fired.

That was the most important leadership lesson of my entire naval career. I never again failed to speak up if I thought I—or anybody who worked for me—was being left out of something that we should be involved in. And I also never fired anyone without first giving a warning and explaining what needed to be done for improvement.

The years went by, and I continued to get promoted, and I got promoted to captain and transferred to Japan. One night in December 1996, I was listening to Armed Forces Radio, and the announcer said, “Country music singer Faron Young has shot himself, and he’s not expected to live.”

I sat up in shock. I’d just talked to Faron several months before that. I had called him and told him I was being transferred to Japan. I said I’d wanted to stay in Washington, D.C. I’d never before had back-to-back tours in the same place, and I liked it there. But the Navy needed me in Japan.

Faron said, “Isn’t that just like the military? You tell them you like where you’re at, you tell them you like what you’re doing, and they ship your ass to Japan.”

Well, after Faron died, I started thinking about writing his biography, because I didn’t want him to be forgotten. But I didn’t know how to write a biography, I didn’t know anything about publishing, I didn’t know anybody in the music business. When I moved to Los Angeles in 1999, I just started working on it. Started making phone calls and trips to Nashville. I picked 2007 as the publication date. That would have been Faron’s 75th birthday, and I thought, that’s far enough in the future that people won’t always be asking me if I’ve finished writing the book. Is it published yet? And, maybe by then, I’d figure out how to write a biography.

I only knew that I wanted to have a book release party in Nashville, and I wanted to have a concert by Faron’s band, the Country Deputies. But at that time, I didn’t even know who they were or how to find them. I didn’t know how I would get there. I just knew that it would happen eventually.

And it did. In November 2007, we had the book release party for Live Fast, Love Hard: The Faron Young Story in the Ernest Tubb Record Shop in Nashville, and the Country Deputies put on a concert that night on the Ernest Tubb Midnite Jamboree. A dream come true.

By that time, I’d already been working for two years on the biography of Marty Robbins. He was also one of my favorite singers. Two things intrigued me about him in addition to his music career. His NASCAR career and his combat service in World War II in the South Pacific in the Navy. I wanted to research both of those.

And also, I got some help when I was writing that from Sherwin, because he was a member of Marty’s Army, the fan club. He let me borrow his whole boxful of Marty Robbins fan club newsletters while I was researching his biography.

We had the book release party for Twentieth Century Drifter: The Life of Marty Robbins in Nashville at the Country Music Hall of Fame in 2012.

Now I’m working on my third biography for the University of Illinois Press. My subject is Randy Travis. So if any of you have any stories that you think should be in Randy’s biography, or if you happen to have any audio or video clips of any interviews he did, I would love to talk to you.

Also, I publish a biweekly country music newsletter—email—that has interviews and news blurbs and letters from my readers around the world. You can sign up for that—free—at the table down here where I’ll be autographing books after the show is over.

I thank you all for being here today, and I thank Sherwin for inviting me.